Having spent half his life behind a mastering console, Stephen Marsh is a master of mastering. Artists welcome his musical, collaborative approach to mastering and his substantial credit list places him among the top of his field. His dual passions for music and technology continue to propel his career and facility into the future. His studio, Marsh Mastering, is located in the Hollywood Hills of Los Angeles California and is known worldwide for an exceptional customized processing chain, accurate clocking and conversion, and a finely tuned critical listening environment that is creative, private and professional.

With nearly two decades and thousands of commercial releases to his credit; Stephen’s track record mastering successful albums with a genre-diverse cross-section of artists includes work with Los Lobos, Boyz II Men, Ben Harper, Kenny Loggins, Megadeth, The Donnas, Ozomatli, Pharcyde, Incubus, Ginuwine, Keb’ Mo’s 2004 Grammy winner ‘Keep It Simple‘ and Jars Of Clay’s 2010 Grammy Nominee and Dove winner ‘The Long Fall Back To Earth‘. Stephen’s mastering with first-call composers includes albums with Alexandre Desplat (Argo), Mychael Danna (Life of Pi – Oscar® and Golden Globe® winner for Best Original Score), Aaron Zigman (Sex and The City), Christophe Beck (The Hangover), Rolfe Kent (Sideways), Mark Isham (42), John Powell (Rio), Cliff Martinez (Contagion), Blake Neely (The Mentalist), and Jon Brion (ParaNorman). Audiophile Remastering credits include Bob Dylan, James Taylor, The Byrds, Nat King Cole, Neil Diamond, Crosby Stills & Nash, Heart, Bad Company, Dio, Yes, Phil Collins, Janis Joplin, Joe Walsh and Donny Hathaway.

With nearly two decades and thousands of commercial releases to his credit; Stephen’s track record mastering successful albums with a genre-diverse cross-section of artists includes work with Los Lobos, Boyz II Men, Ben Harper, Kenny Loggins, Megadeth, The Donnas, Ozomatli, Pharcyde, Incubus, Ginuwine, Keb’ Mo’s 2004 Grammy winner ‘Keep It Simple‘ and Jars Of Clay’s 2010 Grammy Nominee and Dove winner ‘The Long Fall Back To Earth‘. Stephen’s mastering with first-call composers includes albums with Alexandre Desplat (Argo), Mychael Danna (Life of Pi – Oscar® and Golden Globe® winner for Best Original Score), Aaron Zigman (Sex and The City), Christophe Beck (The Hangover), Rolfe Kent (Sideways), Mark Isham (42), John Powell (Rio), Cliff Martinez (Contagion), Blake Neely (The Mentalist), and Jon Brion (ParaNorman). Audiophile Remastering credits include Bob Dylan, James Taylor, The Byrds, Nat King Cole, Neil Diamond, Crosby Stills & Nash, Heart, Bad Company, Dio, Yes, Phil Collins, Janis Joplin, Joe Walsh and Donny Hathaway.

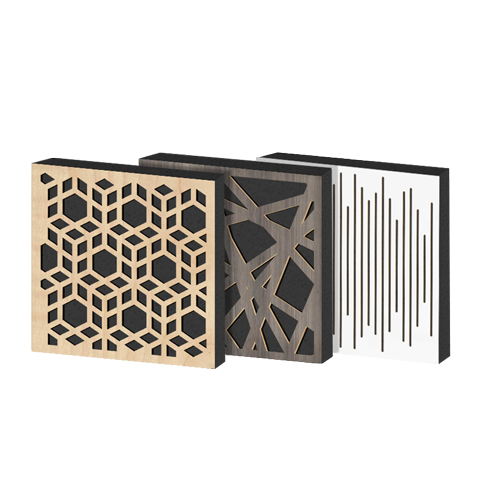

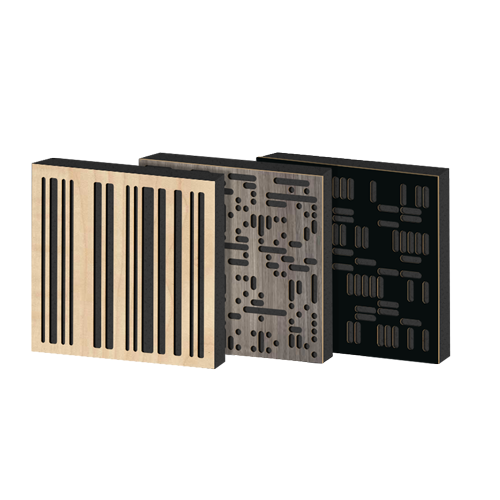

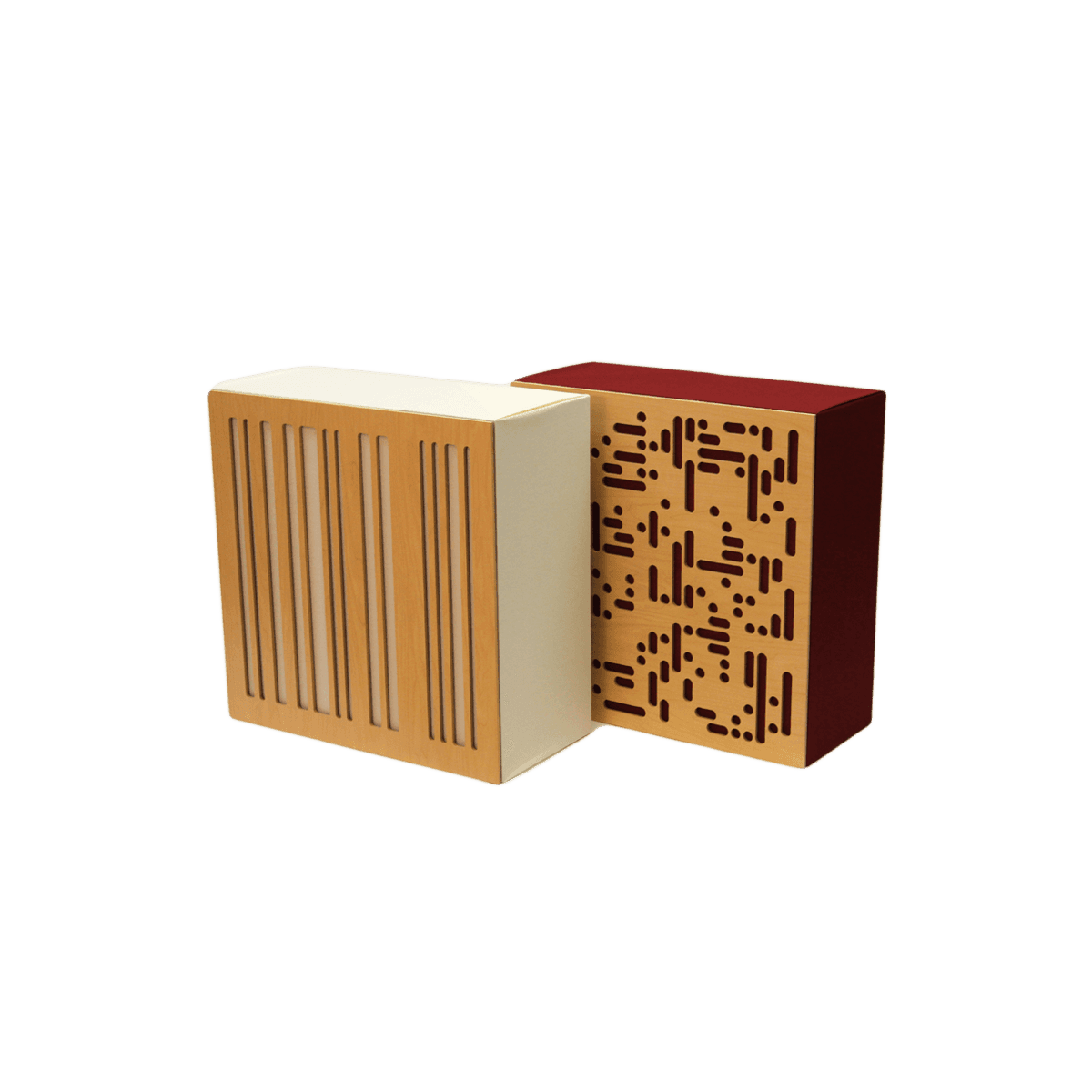

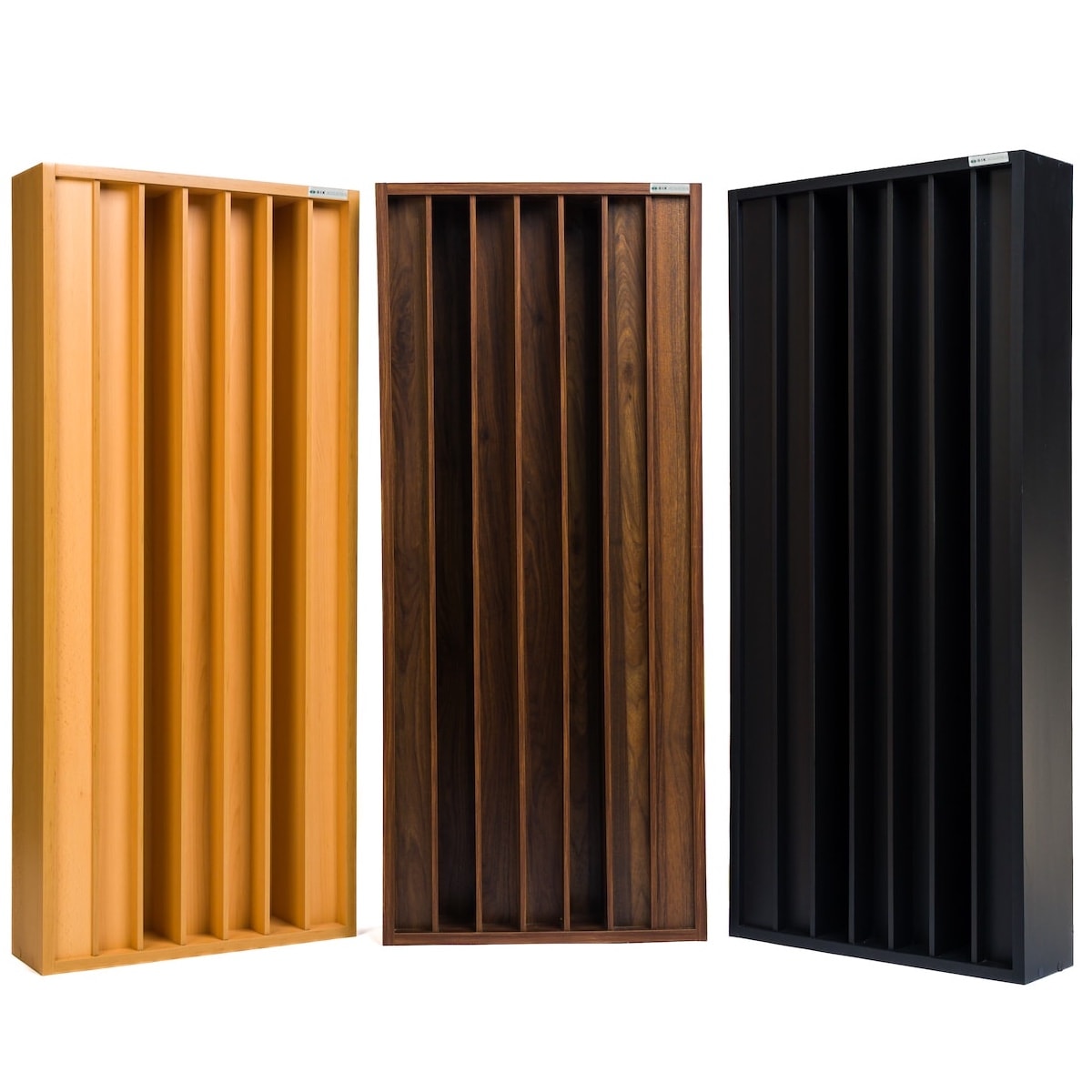

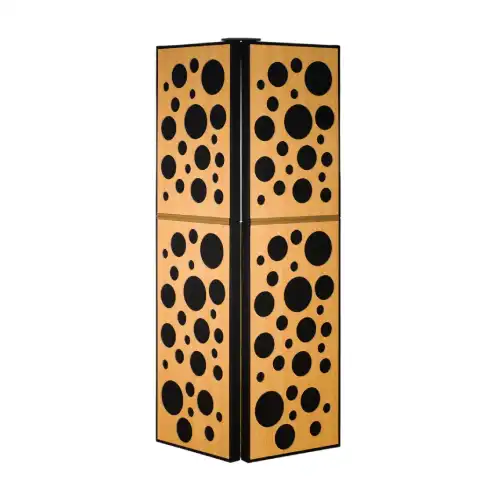

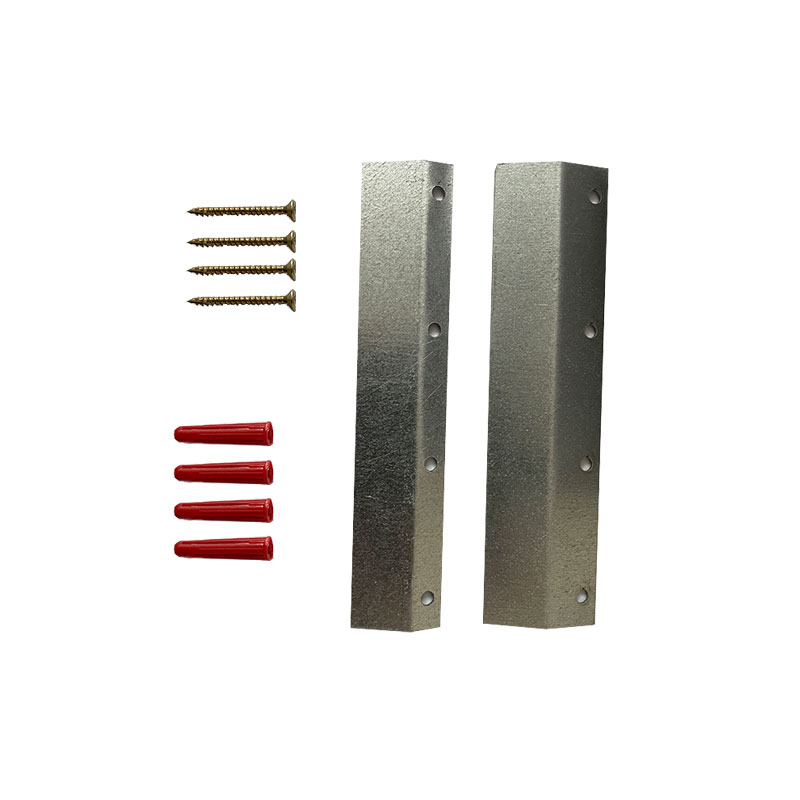

From an equipment standpoint, Stephen chooses things he can count on. “Reliability and product consistency is critical.” He recently installed a bevy of GIK Acoustics Q7D Diffusors in his mastering studio to tremendous results.

We had a few questions for this mastering master and found him hard at work in his LA studio.

GIK: You started mastering at the age of 19. Did you know this was something you always wanted to do and how did you discover mastering in the first place? What was your biggest break?

SM: My story starts at a Taco Bell, that was my big break. A friend came in one night and said he was moving to California in a few weeks. He was making the rounds to say his goodbyes. I took stock of my present situation and high-tailed it right out of state with him. He was coming out to attend Musician’s Institute and their PIT program (drums and such). It turns out this school had just put in an SSL room and added a 6 month recording program that was pretty cheap to attend because it had yet to be accredited. I signed up. It was there that I was introduced to ‘Sound Tools’ (what would become ProTools) and Sound Designer Pro which they used for simple mastering. As is the nature of school recording programs competition for time in the ‘hot seat’ is at a premium – there’s a lot of time where you’re sitting in the back of the room watching or listening or more likely, waiting. The back of the room happened to be where the DAW was so I would pop on the headphones and master records for friends of mine back east while I waited for the next rotation to come up.

So that lit the fire, but this was in the days of tirelessly long processing times – to add compression to a single stereo 16 bit aif file could take an hour – to really do the deal you needed to be in an analog mastering suite. Enter the schools bulletin board – old school corkboard in the hallway and a little advert that said ‘Studio Looking for Runner’ and a phone number. The facility was Sony Music Studios in Santa Monica. I called and spoke to a woman named Nancie Boykiss, the studio manager. She told me she had never heard of the school, that she wasn’t looking for anyone and they weren’t hiring but…..she liked my phone voice so I should come down to meet them. Thus began my introduction to the studio business: a three hour interview/tour of the entire Sony Music west coast campus including the offices of Columbia, Epic and Sony ATC publishing. During the introduction I met present day music biz icons like Randy Jackson and Jeff Ayeroff. After I toured the recording studio operation I was both overwhelmed and completely hooked. I left with the instructions to return the following day if I was available as there was ” “always something to do”.

From there I was fortunate to meet and work under four mentors that shaped everything I did and brought me ‘into’ the business. Phil Kaye, a veteran LA studio engineer who ran the overall studio operation – his credit list runs the gambit. David Mitson, Sony’s West Coast Chief Mastering Engineer, whom I began apprenticing with at age 19 and continued working under for 6 amazing years . Vlado Meller, Sony’s East Coast Chief Mastering Engineer, whom I was fortunate to work with over the years on projects including Celine Dion and Barbra Streisand. Lastly Peter Barker, Sony’s Chief of Technical Maintenance. Pete taught me more about studios and audio than I could ever possibly remember.

GIK: Do you feel the role of mastering engineer has changed over the years? And if so, how?

SM: You know it has but it hasn’t. Formats come and go, trends come and go, hardware and software come and go – but the task is the same: to sonically frame a piece of music in accordance with the artists vision. It’s the same whether we’re remastering classic Bob Dylan from analog tapes for the audiophile market or making EDM tracks bang for the club and headphone crowd. The weird part, and the part that I think throws most people off is that, when the engineering and production are solid, most of our direction is coming from the recording itself. I can’t speak for all mastering engineers out there but for me – the mix will generally tell me at least as much as the artist themselves. For the most part, they’ve already said what they wanted to say with the recording, crafting the mix and feel of the song – so that becomes my bible – informed of course by the additional verbal input given by artists and producers directly and what we hear in the room. I like to say as mastering engineers we’re ‘quasi-creative’ because so much of what we do is built on the work of others and is inherently ‘directed’. However, we can also have a lot of freedom to take something to a completely different place if and when appropriate. We hear things differently as a function of coming in at the very end of the process. We’re specifically and intentionally an objective way-station on the way to the commercial consumption. Part creative, part technical, part diagnostic, all of these elements culminate in the mastering room with the goal of presenting the artist to their audience in that artist’s chosen voice nothing added nothing taken away.

To relate mastering to mixing, I like to say that if mixing is listening from the ‘inside out’ – controlling all the bits individually and balancing them into the whole – then mastering is ‘outside in’ listening. A chance to step back, take all those blended bits back into a human being and then apply subtle tonal balancing to bring out the best in the music. This function of the Mastering Engineer – a crucial editing ‘gut-check’ before release – hasn’t changed since I began and I don’t see it changing any time soon. More and more artists are recording in a less-structured fashion, often DIY style while simultaneously music playback and delivery systems are improving in quality by leaps and bounds. Given this construct, the contribution modern mastering can afford a project cannot be underestimated. It has opened the business up for a whole new generation of mastering engineers – rising to meet the increased demand for mastering all across the globe.

GIK: One thing you can guarantee as a mastering engineer is variety – and you’ve worked on everything from pop albums to film soundtracks to classic reissues. Knowing the relationship between a mastering engineer and client will very much depend on who the client is, what is your approach to working on such varied projects?

SM: I’ve had the fortunate pleasure of only ever being ‘pigeonholed’ for doing things that I actually LOVE doing, like film score albums or reissues specifically for the audiophile market. I’d say the approach to mastering remains fairly similar. I’m never looking to fit anything into a mold it wasn’t intended to fit in, so my overall approach is fairly ‘do no harm’ and I don’t generally deviate from that without a specific request. It is true however that some rudimentary things change from project to project. For instance, when mastering audiophile releases we use NO compression, none. No Compressors, limiters, maximizers or clipping converters – nothing to impede the original dynamic content of the program, just as the artist saw fit to lay it down in original mix. That single thing in my mind sets audiophile mastering apart from mainstream commercial releases. You get the full dynamics and natural tonal balance of the mix without compromise. Whereas we may give a little squeeze to something on a pop track to make it louder – we do absolutely nothing beyond good gain staging within the chain for level, volume simply isn’t a dominating concern.

When you remove the requirement that something be made ‘loud, but still good’ which is kind of a standard request – you wind up getting to spend all your time just making it sound… well, good. That opens the door a bit further to making something that’s actually ‘great’ in my mind. To put it another way – I can make really good sounding records that are also really loud – but it’s much more challenging to make a really loud record sound ‘great’. It can be done and done well but, at a certain point the loss of dynamics can no longer be overcome in a musically pleasing fashion and you have to give up some of the good stuff, the stuff that lives in the shadows of the recording – the space in between the notes, in the name of loudness.

Now I don’t hate loudness, some music needs that push or it won’t feel right. I also don’t favor the sound when it’s taken too far. The way I see it, awareness of the ‘loudness wars’ is now fairly broad and if an artist in this day and age decides to push it – it’s a creative decision over which they have ultimate control. I’m more inclined to stop a dB or 2 shy and have a conversation with my client before we head too far down the path of loud just for the sake of loud. You do however have to be very careful not to squelch an artist’s creativity in the name or sonic purity if that’s not what the music is about. Finding the middle ground somewhere between knowledgeable sonic judge & jury and wide-eyed, open-minded musical conspirator is one of those things that really elevates the best mastering engineers above the pack.

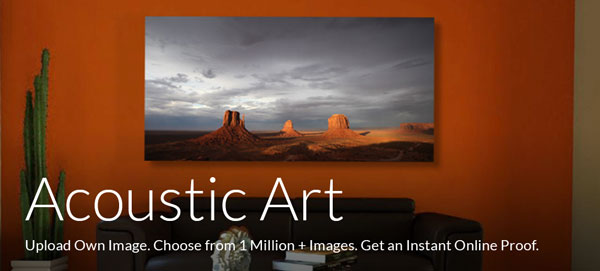

GIK: Mastering requires critical listening and the results depend upon the accuracy of speaker monitors and the listening environment. In your own words, “Mastering rooms aren’t designed like recording studios. They aren’t designed to enhance what’s coming out of the speakers and make it sound really pretty… they’re really designed to just lay bare what’s going on.” So how has GIK helped your listening environment?

SM: For a music junkie like myself – there are few things quite as skin-tingling as sitting next to Golden Globe® & Academy Award winning composer Mychael Danna and hearing the culmination of two full years of his life creating the musical landscape for the film Life Of Pi. To hear maybe 100+ musicians from around the globe come to life in the room, to get to hear what he heard in his head – exactly as he heard it in a fully orchestrated form – that’s magic.

SM: For a music junkie like myself – there are few things quite as skin-tingling as sitting next to Golden Globe® & Academy Award winning composer Mychael Danna and hearing the culmination of two full years of his life creating the musical landscape for the film Life Of Pi. To hear maybe 100+ musicians from around the globe come to life in the room, to get to hear what he heard in his head – exactly as he heard it in a fully orchestrated form – that’s magic.

Through my working relationship with fellow mastering engineer Steve Hoffman, I’ve had the opportunity to work on some audiophile album reissues that have been just incredible. Sitting in a well tuned room and hearing Suite: Judy Blue Eyes roll through a pristine chain from the original 1969 ¼” master tape, a song I’ve heard since my youth and to hear it in a whole new way – the REAL way – it’s just incredible. In both instances the common element that both share is the room – it all comes down to the room. Everything else will be different. It’s paramount you have a room you can trust and I can trust my GIK room.

Through my working relationship with fellow mastering engineer Steve Hoffman, I’ve had the opportunity to work on some audiophile album reissues that have been just incredible. Sitting in a well tuned room and hearing Suite: Judy Blue Eyes roll through a pristine chain from the original 1969 ¼” master tape, a song I’ve heard since my youth and to hear it in a whole new way – the REAL way – it’s just incredible. In both instances the common element that both share is the room – it all comes down to the room. Everything else will be different. It’s paramount you have a room you can trust and I can trust my GIK room.

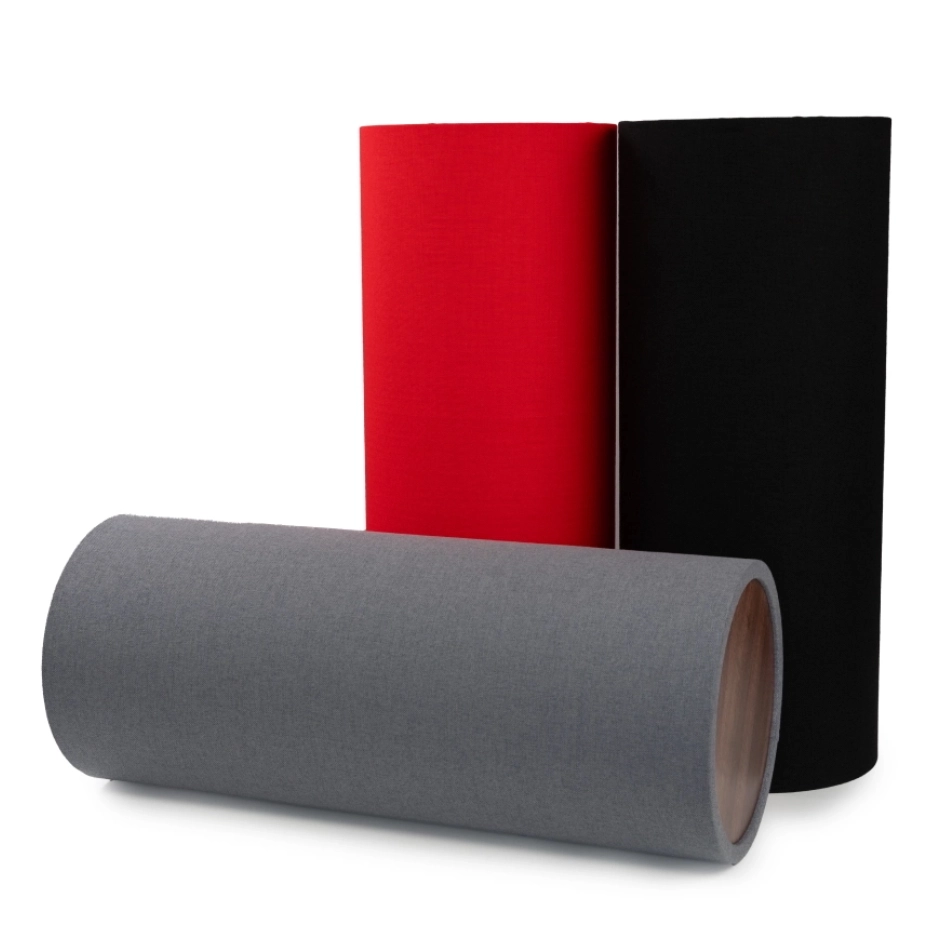

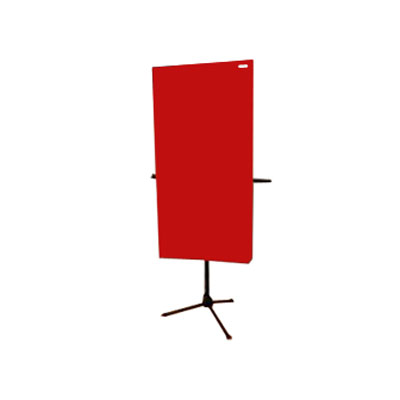

Every critical listening environment is going to have certain combination of absorption, reflection and diffusion to give it a sonic signature suited to the work done there, that’s primary. My next goal in a mastering room is to create an environment free from distraction – and that includes acoustical distractions so it encompasses the primary goal and I view them as deeply related. Anyone who has tried to ignore a dripping faucet at bedtime knows what I’m talking about. A weird room mode or modes making things uneven, over or under-trapping, noisy neighbors, electrical issues, equipment troubles, a weird rattle, a buzz – all these things impede the engineer’s and artists ability to let the outside world vanish and work on their art. Everything from the acoustics, ergonomics, the power and grounding- everything requires extra attention in any mastering room.

What I really love about GIK, and also I love telling people this is that after years of working in mastering rooms designed by studio acoustics legends – my new room was designed by a fellow from St. Louis whom I’ve never met and has never actually set foot in my room… and it’s the best sounding room I’ve ever worked, period. All due respect to the old-school, I love those guys – but the new school has got it going on too. Thanks to GIK acoustician Bryan Pape, for the first time ever I can hear and feel every bass frequency through to the lowest notes and the top end is smooth and wide. The midrange takes on a natural, 3-dimensional quality so I can hear relationships between instruments and voice in a way unlike before. All the frequencies just feel right against each other and the room reacts in such a predictable fashion that I’m able to work faster and with fewer revisions. That’s huge.

Bottom line – I gave Glenn and Bryan a clear idea of our workflow, the confines we would be working within and what I had preferred in past rooms, and they just freakin’ nailed it. GIK gave me the first mastering room in 19 years that I could simply trust without having to ‘translate’ it.

GIK: We’re very proud to have worked with you on the project. What sort of advice or tips you would offer to engineers or artists who are undertaking the mastering process?

SM: Be aware, seek knowledge – but don’t get too bogged down shopping for an engineer. Beyond the routine stuff like a verifiable credit list, a suitable listening environment and the right tools to do the job, you’re basically looking for two things. 1) a person you feel you can communicate with freely and openly about your music and then let them go to it and 2) a person you feel confident working with if you don’t love the engineer’s take on the first pass. I CANNOT stress this enough – if you’re not comfortable both telling your engineer you think something sounds like crap and confident in their abilities to fix it should you be unhappy – find another one immediately! The engineer will be able to offer you more and better options if they know exactly where you stand. Communicate then trust but, verify with your ears. At the end of the day it should still sound like your music.

The other trap I recommend avoiding is in trying to learn how to do everything yourself. DIY can work, but will it yield the best results and will it best serve your ultimate goals as an artist? One of the most important tools any mastering engineer can bring to the table is an objective point of view. There’s no way an artist can fake like they haven’t heard a mix after 2 months recording and 2 weeks tweaking. With so much information out there on anything and everything it’s only natural to try to learn and do as much yourself as possible. The downside, as I experience it, is that you divest yourself of one of the things that makes music creation so magical – the fuzzy math that occurs when you put a group of specifically talented creative human being on a project together and you come out with a sum total that is greater than any of the individual parts; adding 1 + 1 + 1 and getting 5. That can only happen when human beings explore their music and sonic worlds together.

If it’s true that beyond the limits of your present is your potential – playing it safe in your own world will only ever get you so far. Bringing an expert in here and there doesn’t make you any less of an artist, quite the opposite. We brought in GIK to make our new mastering room sound amazing and they delivered. Bringing in the right people can make your creativity blossom in ways you hadn’t imagined.

In Spring 2014, Stephen Marsh had a chance to install the PreSonus Sceptre S8 Monitors in his studio and put them through their paces. Here, he shares his reaction.